Fixxx

Moder

- Joined

- 20.08.24

- Messages

- 1,042

- Reaction score

- 4,023

- Points

- 113

A vulnerability discovered by researchers in Android allows apps to steal passwords, one-time codes and other secret information from the screen without requiring any special operating‑system permissions. Restrictions on apps in Android are continually tightened so that fraudsters cannot use malware to steal user's money, passwords and private secrets. But a new vulnerability, called Pixnapping, bypasses all layers of protection and allows an attacker to silently read pixels from the screen - effectively taking a screenshot. A malicious app with no permissions at all can see passwords, bank balances, one‑time codes - in short, anything the device owner sees on the screen. To date Pixnapping (CVE‑2025‑48561) is likely to affect all modern Android smartphones, including those running the latest Android.

What is Pixnapping Vulnerability

Why screenshots, screen streaming or screen reading are dangerous As demonstrated by the OCR stealer SparkCat we discovered, attackers have already mastered image processing: if there is an image on a smartphone that contains valuable information, it can be found, its text recognized on the device and the extracted data sent to the attacker's server. SparkCat is notable for having slipped into official app stores, including the App Store. For a malicious app armed with Pixnapping, repeating this trick would be easy, since the attack doesn't require special permissions. An app that honestly performs some useful function could quietly and unnoticed stream one‑time multi‑factor authentication codes, crypto‑wallet passwords and any other information to fraudsters. Another common attacker tactic is to view the needed data in person in real time. For that, the victim receives a call in a messenger and is persuaded under various pretexts to enable screen sharing.

How the Pixnapping Attack Works

Researchers managed to screenshot other apps by combining previously known methods of kidnapping pixels from browsers and from ARM smartphone video accelerators. The attacking app silently draws semi‑transparent windows over the target content and measures how the video system composes the pixels of layered windows into the final image. As early as 2013 an attack was described that allowed one site to load another into part of its window (via iframe) and, by performing permitted overlay and image‑transformation operations, compute what was drawn and written on the other site. That attack is not possible in modern browsers, but the U.S. research team devised how to apply the same principle to Android.

- First the malicious app sends a call to the target app. In Android this mechanism is called an intent. An intent is commonly used not only to launch an app but also, for example, to open the browser on a specific web page or a messenger inside a chat with a particular contact.

- The attacking app sends the call to cause the target app to draw the desired information on screen. Special hidden‑launch flags are used, after which the attacking app sends an intent to launch itself. This combination of actions allows the target app to not appear on screen at all while it renders, in its window and in the background, the information the attacker needs.

- In the second stage the attacking app draws a series of semi‑transparent windows above the hidden target app’s window, each of which covers and blurs the content beneath. This layered composition is still invisible to the user, but Android still computes how such a combination of windows should look if the user brought it to the foreground.

The attacking app can only read pixels from its own (semi‑transparent) windows; the final composition that includes the image from the target app’s window is not directly accessible to the attacker. To bypass this limitation, two tricks are used.

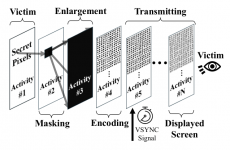

First, the pixel to be stolen is isolated from its surroundings by rendering an opaque overlay with a single transparent pixel in the desired location above the target app, and then an magnifying layer with strong blur is placed on top of that combination.

*diagram of Pixnapping vulnerability (CVE‑2025‑48561)

To determine which pixel lies at the very bottom in this jumble, the researchers used another known vulnerability called GPU.zip (this is a link to a description site, not a file). It's based on the fact that all modern smartphones compress any image data sent from the main CPU to the video accelerator. This compression is lossless, like ZIP files, but the speed of compression and decompression changes depending on what information is being transferred. The GPU.zip vulnerability allows measuring the time taken to compress the data and thereby guessing what data is being transmitted. Using GPU.zip, the isolated, blurred and enlarged pixel from the target app’s window can be read by the attacking app. To steal anything meaningful the process must be repeated hundreds of times, for each pixel separately. But this is quite feasible in a short time - in a video demonstration of the attack a 6‑digit code from Google Authenticator is extracted in 22 seconds, while the code is still valid.

How Android Protects Screen Privacy

Google engineers have nearly 20 years of experience defending against various privacy attacks, so layered protections against unauthorized screenshots and video capture exist.

A full list of measures would take several pages, so here are some examples:

- The “secure window” flag prevents system screenshots;

- Access to screen‑casting tools (MediaProjection) requires explicit user confirmation and can only be performed by an app that is visible and active;

- Strict limits on access to administrative services like AccessibilityService and on drawing over other apps;

- Automatic hiding of one‑time passwords and other secrets when screen casting is active;

- Restrictions preventing some apps from accessing other app's data, including the impossibility of requesting a full list of installed apps.

Which Devices Pixnapping Works On and How to Protect Yourself

The attack was tested on Android versions 13 through 16 on Google Pixel devices from generation 6 to 9 and on the Samsung Galaxy S25. The researchers believe the attack will work on other Android devices as well - all mechanisms used are standard, although there are implementation nuances in the second phase of the attack (the magnification of pixels). Google was notified of the attack in February and released a patch in September. Unfortunately the chosen mitigation proved insufficient, and researchers quickly found a way to bypass the patch. A new attempt to fix the vulnerability is planned by Google for the December security update release. As for GPU.zip, no vendor has announced plans to patch that leakage channel - at least none have done so since 2024, when the defect became known. User's options to protect themselves from Pixnapping are limited.

Recommended measures:

- Update promptly to the latest Android version with all security fixes;

- Avoid installing apps from third‑party sources and be cautious even in official app stores when an app is very new, has few downloads or a low rating;

- Ensure you have a full device‑security solution installed on your smartphone.